A portrait of Krishna in the style of Graciela Rodo Boulanger via Midjourney.

Many Hindus are wondering what potential role sacred images generated with AI can play in spiritual life. Hindu sacred imagery is more than decoration. It is rooted in ancient meditative insights and carefully preserved traditions. As technology changes how images are created, questions emerge about accuracy and authority. At the heart of the discussion: Can AI-generated imagery be used in worship?

Can Hindus venerate a deity using an AI-generated image?

In Hindu Dharmas, if an image of a deity is to be used in veneration, it should be an interpretation of the dhyāna mantra of the deity — a meditative visualization which is interpreted to make the physical image of the deity. Only humans have the devotional capabilities necessary to make such an interpretation through meditation. As AI has no capacity to meditate, it cannot tap into the aspects of reality that humans can access in this way.

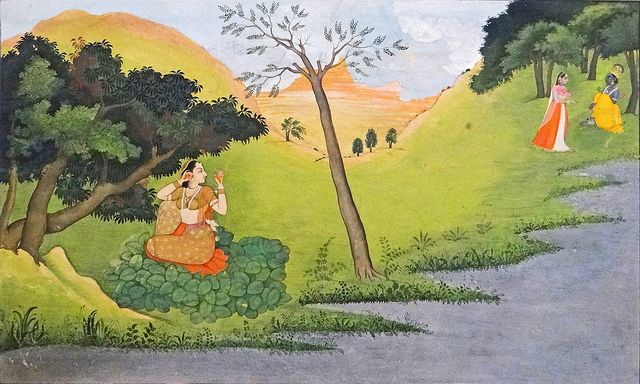

A print reproduction of a painting of Ram Parivar

That said, in some limited circumstances — rarer deities, there are too many to name, for which it is harder to find existing painted images, for example — the use of AI-generated images may be acceptable as a last resort.

There is important caution in this: If an AI-generated image is to be used, it should be prompted based on the dhyāna mantra, and considerable time should be taken to refine it to ensure its iconographic accuracy.

Are AI-generated images of Hindu devatas actually accurate?

With careful prompting by someone with real expertise in Hindu iconography, AI can generate images that can be quite beautiful and without error. However, this isn’t usually the case. More commonly, AI introduces distortions or stylistic changes that a human artist creating a traditional Hindu figure would never do.

What’s more, because it is drawing upon and combining a huge array of images that already exist in order to respond to the prompt, most AI-generated images have an uncanny similarity in flattened expression. Interestingly, when asked to create Hindu images, most AI current models seem to pull in elements of Tibetan Buddhist imagery, as well as other traditions, not understanding the nuances between these different iconographical traditions. As these images become more commonplace, there is a real risk that inaccuracies will be codified as correct by AI models.

Why does it matter if AI-generated images of Hindu deities are accurate if my devotional intent is sincere?

There is a real and intrinsic value in the correctness of the image, independent of sincerity of devotional intent.

Hindu sources of knowledge explicitly state that Hindu sacred images are not arbitrary or purely creative artistic outputs of human imagination. Rather, they are based on genuine spiritual perception, going back to ancient rishis (spiritually enlightened sages and teachers).

From the Vāstusūtra Upaniṣad: “It is in the mind of rishis, who see and have the power of discerning the essence of all created things of manifested forms […] They see the different characters, the devas and the asuras, the creative and destructive forces, in their eternal interplay. It is this vision of the rishis, of the gigantic drama of cosmic powers in eternal dynamism, from which the image-makers drew the subject-matter for their work.”

Thus, in choosing an icon for veneration, ideally it should be carved, painted, or drawn by a skilled craftsman who knows the traditional forms for creating such images.

If your intent is to venerate, say, Ganesha and that intent is coming from the heart, that is great. However, all sources of knowledge on Bhakti Yoga specify that it is still important to correctly observe traditional ceremonial methods and procedures. Only after some time, once one attains the supreme devotional state of Parābhakti these methods may naturally fall away, but it is counterproductive for a non-advanced practitioner to prematurely adopt this attitude.

Hasn’t Hindu imagery evolved over the centuries? Aren’t AI-generated images just a continuation of this?

Yes, in a way — Hindu imagery has evolved considerably over time — but AI brings important challenges and cautions that must be taken seriously.

Some Hindu Dharma traditions use images and some do not, and those that do, use them in various ways. In many traditions, images of the Supreme Being or Illumined Beings are deeply tied to ceremonial veneration. In ancient times, millennia ago, images might be rare, expensive, and mostly found in temples rather than homes, other than images made by individual householders, which were usually simpler sculptures or abstract representations. Over time, regional styles and influences (such as Gupta elegance or Chola bronzes) created distinct visual vocabularies.

As foreign cultural influences moved into India, representation shifted, incorporating new stylistic elements. Mughal influences, for example, introduced changes such as female figures being depicted wearing stitched blouses rather than older, more traditional Hindu clothing. Skin tones in art also shifted, from many dark complexions in ancient art to lighter tones.

The 19th century marked a dramatic shift. Raja Ravi Varma created images of Hindu deities in a naturalistic style, influenced by European realism. His art humanized the deities while maintaining divine grandeur. When the printing press allowed relatively inexpensive mass production of posters, calendars, and devotional booklets, suddenly Hindu images could easily be everywhere, on walls, in shops, even part of political campaigns. Many households could now have colorful sacred images of Lakshmi, Saraswati, and many other forms of the Divine. However, this widespread availability of sacred imagery occurred during a time period where exceptionally light skin tones had become fashionable, in accordance with Colonial-era aesthetics. Working in this cultural context Raja Ravi Varma produced imagery with dramatically lighter skin tones than had been the norm historically in paintings. In doing this he unintentionally introduced a colorism in Hindu art that still persists to this day.

A century later, as access to the Internet became commonplace, with all but the absolute poorest Hindus having the ability to access a wealth of sacred imagery on mobile phones, the circulation of Hindu images has exploded. Representations of the Divine that were once bound to geography or community now circulate globally within seconds. Digital editing also means anyone can modify traditional imagery, sometimes respectfully, sometimes carelessly, blurring lines between sacred representation and pop culture.

Today, AI-generated images open new possibilities but also create troubling risks. Algorithms trained on imperfect or biased datasets may produce nominally Hindu images but ones that critically distort tradition. The ease of generation means these distorted images can spread as fast as accurate ones. When enough people see distorted representations, they risk becoming accepted as correct. And at the same time as more distorted iconography gets created, AI models begin codifying these distortions again and again.

Over time this will reshape cultural memory, doing so in a way that is fundamentally different and flawed compared to the evolutions in Hindu imagery that have previously happened, through the interplay of human aesthetic and spiritual cultures, preferences, and experiences.

This raises urgent questions: What is authenticity in the digital age? Who curates it, decides what is authentic? How do we protect traditions when technology makes endless reproduction effortless, while just as effortlessly amplifying and codifying inaccuracies?

What if I just want a beautiful image of one of the devatas to use as my phone wallpaper, not for veneration? Is that alright?

Yes, it would be. The guidance above is specifically for images used for purposes of veneration, not for images intended for purely decorative purposes. Additionally, HAF has provided updated guidelines for images used for commercial purposes, which now includes a section on AI-generated images.

However, the previous cautions about accuracy in iconography still apply. Without careful refinement, AI generated images very well may have errors of representation. In a strictly artistic sense these may be subtle at times and not necessarily detract from the beauty of the image. Over time though, if such inaccurate images become commonplace, AI models may well start taking these images as correct, not picking up on the errors originally created. The models will then start creating new images from these inaccurate ones, wrongly establishing the inaccuracies as correct.

A portrait of Sri Ganesha in the style of a Maud Lewis illustration via Midjourney.

Note that in this image, the icon has 6 toes.

What kind of art IS appropriate?

AI-generated art is everywhere, but when it comes to Hindu devotional practice, its use becomes complicated. Hindu images of deities (murtis, paintings, or icons) are traditionally derived from dhyāna mantras—meditative visualizations passed down by rishis. Because AI cannot meditate or spiritually perceive, its creations don’t carry the same sacred grounding.

That said, AI-generated images might be acceptable in limited cases (such as rare deities with few traditional depictions), but only if carefully refined for iconographic accuracy and based directly on dhyāna mantras. However, here’s the order of preference, extrapolated from the Nrsimhatantra, for an icon that has been carved, painted or drawn:

- A spiritual master: someone who knows the traditional dhyānas of the devatā and has likely perceived them directly as well

- A spiritual practitioner: someone who knows the dhyānas

- An artist who is spiritual: someone knows the dhyānas plus abides by the guidelines for materials and forms as prescribed in a tradition

- An artist who focuses on aesthetics primarily

- A reproduction of someone created by any of the above: for example, lithography, photocopies, putting a pic up on the laptop etc.

- Any means informed of the above

Key takeaways

- AI images are not inherently sacred. They lack the devotional grounding of human-created works.

- Limited exceptions exist. However, accuracy and respect are essential.

- Cultural risks are real. Errors within AI-generation content may amplify and overwrite more accurate depictions.

- Intent matters, but….So does following traditional forms, especially for veneration.

- AI is different from historical evolution. It can amplify inaccuracies rather than building on spiritual-cultural contexts.