Naga icon at pond

1) It is known as a day in honor of snakes

Respect for all life is a foundational pillar of spirituality. Nobody knew this better than those of the ancient world. Living in close proximity to the elements, they had an intimate connection with nature, making them keenly attuned to the importance all beings play in a healthy and harmonious environment.

To highlight this, they placed great emphasis on a number of symbiotic relationships humans shared with certain species of animals, including even those that appeared menacing, even serpents and snakes. While this may seem counterintuitive, especially considering the Judeo-Christian symbology of Satan such creatures tend to evoke, the truth is that a medley of cultures revered not only the ecological impact their presence had, but the sacred one.

Potent, astute, and mysterious beings who reside beneath the surface, they were perceived as guardians of treasures one must dig deep to uncover, from the gems and minerals of the earth, to the esoteric truths of spiritual consciousness. As many of the world’s most renowned civilizations — like the Greeks, Chinese, Sumerians, and Nordics — thus held veneration for their respective serpent-gods and spirits, those who followed the Hindu Dharmas did so as well, feeling the naga, or snake, represented a uniquely powerful role in transcendence.

Aside from being depicted alongside popular gods like Shiva and Vishnu, thereby cementing the serpentine form as an aspect of the Supreme, kundalini (the divine feminine force, or shakti, lying dormant within us all) is described as a serpent-like energy that rises through our chakras when awakened, before reaching the crown of the head, opening our higher selves to enlightenment.

The Hindu Dharmas, therefore, observe a variety of snake-centered ceremonies and festivals, like Naga Panchami, which promote an array of stories, lessons, and practices that help bring awareness to the environmental and spiritual significance of serpents.

Read on to learn a little about them.

King Parikshit killed by Taraksha

2) It commemorates the day Janamejaya was stopped from destroying the serpent species

If honoring the significance of snakes is what Naga Panchami is all about, the story of how they were almost wiped off the face of the planet is a pretty good place to start.

According to legend, there was once a great warrior-king named Parikshit who, while training in the forest, came across the hermitage of a distinguished sage called Samika Rishi. Overcome by hunger and thirst, Parikshit asked Samika for some water, but as the sage was totally absorbed in the trance of meditation, the king’s presence went completely unnoticed. Insulted by Samika’s negligence, Parikshit resigned himself to leaving, though only after draping the body of a lifeless snake around Samika’s shoulder to express his indignation. While the king’s offense would never have been taken seriously by the sage, before he could break out of his trance, Shringi, his young son, discovered what had happened. Infuriated by the transgression to his father, the boy recklessly lashed out, cursing the king to meet his end in seven days by snakebite.

As it happened, Parikshit, upon returning home, knew he had let his fatigue get the best of him, and profoundly regretted what he had done. Upon receiving news of his imminent death, he therefore chose to embrace it. Surrounded by all the illustrious sages of the land, he situated himself on the banks of the Ganges, and immersed himself in spiritual discourse. When, thus, after a week’s time, a serpent by the name of Taraksha came to kill him, Parikshit was completely fearless, at peace, and fully realized.

Unfortunately, Janamejaya, Parikshit’s son, didn’t quite feel the same way. Aggrieved by his father’s death, he swore to enact revenge on not just Taraksha, but the entire serpent species, and began conducting a great and powerful sacrifice that would vanquish them all. As the sacrifice progressed, however, pulling one snake after the next into its flames, Astika, a young and wise sage born of a human father and naga mother, approached the sacrificial arena, equipped with the unique perspective of his dual heritage. Feeling both compassion for the snakes, and a keen sense of how to appeal to the sages, he submissively glorified the new king and his priests, highlighting their honor and virtues. Indeed pleased by his eloquent and humble demeanor, Janamejaya offered to grant a boon to Astika, who promptly asked the serpent genocide be put to a stop. And so it was, albeit reluctantly.

Needless to say, reluctance towards the survival of snakes isn’t the lesson one is meant to take from this story. Blinded by despair, Janamejaya launched a crusade of vengeance towards an entire species, fixated on the fact one of them stole the life of his father. Yet, he failed to realize Taraksha was more than just a mundane bringer of death. Motivating Parikshit to delve into the deepest of topics, the serpent’s impending arrival was actually a great blessing in disguise, as his fatal bite ultimately granted access to the next glorious phase of the king’s spiritual journey.

Snakes, therefore, are meant to be seen as sacred symbols of divine exploration, whose piercing nature can help propel us through turbulent gateways of spiritual transformation.

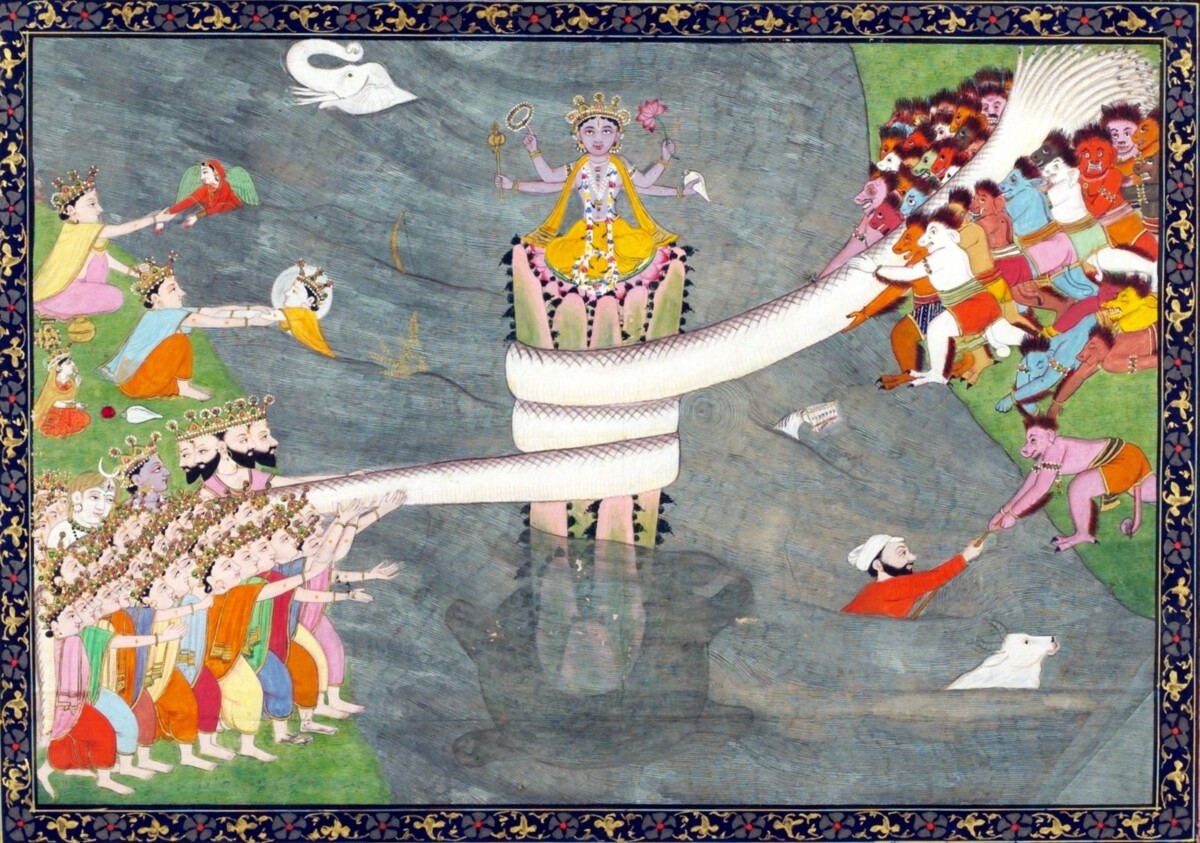

Vasuki being used as a rope to churn the milk ocean for the nectar of immortality

3) It commemorates Vasuki and the churning of the ocean of milk

The battle of life’s positive and negative forces is explored in a variety of ways throughout Hindu teachings, often taking on universal proportions in a long-standing struggle between the devas (divine beings) and the asuras (their power-hungry enemies). And so it was during a critical episode of this struggle another pivotable snake appearance took place, following a time the devas, who had been severely weakened by the curse of a sage, were on the verge of total defeat.

Desperate for help, they approached Vishnu (the sustainer of the universe), who advised them to broker a truce with the asuras, for if the two parties combined their energies, they could produce a nectar of immortality that would restore the strength of the devas. Though the asuras had the upper hand, the idea of an immortal nectar was too tempting for them to pass up. When the devas, therefore, approached them with the proposal, they swiftly agreed, prompting the opposing sides to immediately start working.

Told the elixir could be generated out of a divine ocean of milk, the devas and asuras, along with help from Vishnu himself, carried a golden mountain called Mandara to its waters to use as a churning rod. Needing, however, a method by which to twist it, and knowing that not just any rope would do, they summoned Vasuki, a king of the serpents powerful enough to handle the task. Thus coiling him around the mountain, the devas grabbed his head, the asuras grabbed his tail, and they enthusiastically began pulling him back and forth, churning the golden summit, eager for the result. And despite almost dying from the arduous process, the serpent held strong, as his invaluable contribution eventually led to the nectar they all hankered for.

Of course, to many, Vasuki’s role in this story goes beyond his mere utility as a rope. Humanity is deluged in the eternal struggle of dark versus light, and in order to attain life’s deeper truths we must learn to steady this struggle within. Like the slithering line that provides balance to the opposing yet interdependent energies Yin and Yang represent, Vasuki was the balancing agent between the devas and asuras, showing that the elixir of our highest spiritual potential can be accessed if we imbibe the flexible, potent, and enduring nature of a snake.

Krishna dancing on Kaliya’s hoods

4) It commemorates the day Krishna defeated Kaliya

If you’ve made it this far, hopefully you’ve overcome whatever spiritual misconceptions you had about snakes, and have embraced the benefits of finding your inner serpent. Yet, fierce as such power can be, it’s important we learn to control it, so it can be used to amplify our spiritual aspects instead of our destructive ones. Because of this, Hindu teachings are filled with narratives that convey the emphatic quelling of toxic behavior, with one that holds a special place in the heart of those who observe Naga Panchami. One that takes place in Vraj, the sacred land of Krishna.

Home to Vrindavan, the village where the Divine being is said to have grown up, Vraj’s pristine forests, hills, rivers, and lakes, served as the cherished settings of his childhood pastimes, where he and his cowherd friends engaged in various devotional exchanges revered by followers all over the world. Once, unfortunately, one of these lakes became inhabited by a great serpent named Kaliya, whose poison was so toxic the water would boil, creating vapors that killed the vegetation and wildlife of the surrounding area. Deciding, therefore, that something had to be done, Krishna fearlessly jumped into the lake, and began splashing about, provoking the serpent into battle.

Angered that someone had trespassed on what he believed to be his territory, Kaliya quickly took the bait, and furiously bit the child, enveloping him in his coils. Completely unaffected, however, Krishna seamlessly freed himself from the serpent’s grip, and eventually rose from the water, climbing on top of him. There, he began to dance on his many hoods, subduing his heads with the strength of his divine feet, until Kaliya, on the brink of death, finally took the humble position and surrendered.

Seeing their husband in such a state, Kaliya’s consorts emerged and appealed to Krishna, pleading with him to spare his life. Pleased by their humility, he happily granted their wish, on the simple condition they agree to leave and never return. Thus doing as instructed, Kaliya and his wives departed, allowing the natural balance of the area to be restored — conveying a most valuable lesson.

Yes, the serpent’s power can be menacing, having a poisonous effect within the lake of our minds. But if we remain fearless, using the strength of love, compassion, and forgiveness to stamp out its venomous tendencies, we too can take full control of its energy, directing it towards the illustrious pursuit of our highest spiritual endeavors.

Stone naga at temple

5) It’s celebrated during the lunar month of Shravana

Naga Panchami is celebrated on the fifth day of the bright half of the lunar month of Shravana (July/August), as it’s believed to be the very day Janamejaya’s sacrifice was brought to a halt. Depending on the person, however, one may choose to emphasize a different narrative in connection to the festival, some of the narratives, all of them, or perhaps even none of them. Being that Shravana is the rainy season in India, when snakes are washed from their burrowing homes onto the land of men, there are those who simply spend the day praying for protection and a good harvest.

Whatever one’s focus, the way people honor the day has a relatively similar complexion across various regions of India and beyond. To start, fasting — as is often the case with Hindu celebrations — is observed by many, helping them withdraw from sensory distractions so they can delve deeper into the heart of their meditations. Taking baths in sacred rivers and lakes, devotees chant prayers and mantras for purification. While at homes, images of snakes are drawn on walls and floors, invoking a mood of veneration found also in the myriad temples dedicated to serpent gods, where their icons are given milk, flowers, sweets, and a medley of other offerings.

Going further, communities gather together, organizing fairs and programs to mark the occasion, boasting traditional songs and performances that encompass followers from all walks of life. And countless around the world make a point of not digging up the earth, to avoid the possibility of disturbing or harming snakes that might be living beneath them.

From legends and prayers to gatherings and practices, the day thus encompasses a dynamic range of engagements, inviting all to raise their consciousness toward the serpent species in reverence and respect. For without them, both our material and spiritual lives would not be the same.