Portrait of Lord Curzon, viceroy and governor-general of India.

A Region of Chaos

Bangladesh has been a region of perennial chaos. Maybe you’ve noticed.

Maybe you noticed how, in 2024, Hindu minorities had their homes, businesses, and temples ransacked, vandalized, and burned, following the ousting of former prime minister Sheikh Hasina. Maybe you saw the mobs that assailed them in 1992, after an unused mosque, built on the ruins of a historic temple, was demolished.

Maybe you’ve heard of Operation Searchlight and the massive campaign of genocide that happened during the 1971 war that separated Bangladesh from Pakistan. And maybe you’ve learned about the 1947 Partition of India, one of the bloodiest events in modern history, resulting in millions killed and displaced.

Maybe you know it all and more. Maybe you don’t. Still, whether you sympathize with Hindus, feel inclined towards Muslims, or simply believe the recurring violence between them is part of another cut-and-dried cycle of interreligious extremism, it’s important to understand all that led to its spinning. While though Hindu and Muslims are the ones caught in the wheel, it was, in truth, a third side that thrust it into motion: Great Britain.

Before the early 1900s, Hindu-Muslim conflict wasn’t nearly as entrenched or widespread as it’s been in recent memory. Sure, there were moments of discord, especially during the medieval period with the imposition of jizya (taxes on non-Muslims) and the desolation of temples under Muslim rule. But because a number of leaders, like Akbar, pursued policies of tolerance and even promoted spiritual syncretism, the two communities managed to live entwined for hundreds of years, experiencing long stretches of respect, cooperation, and cultural exchange amongst each other.

This all changed, however, at the turn of the 20th century, when British imperialism was at the peak of its dominion, and India was a territory under its control. An invaluable asset, described as the jewel in the crown of the empire, the colony was, by far, its most profitable, as its resources propelled Britain’s strength and influence far past what they could have possibly imagined.

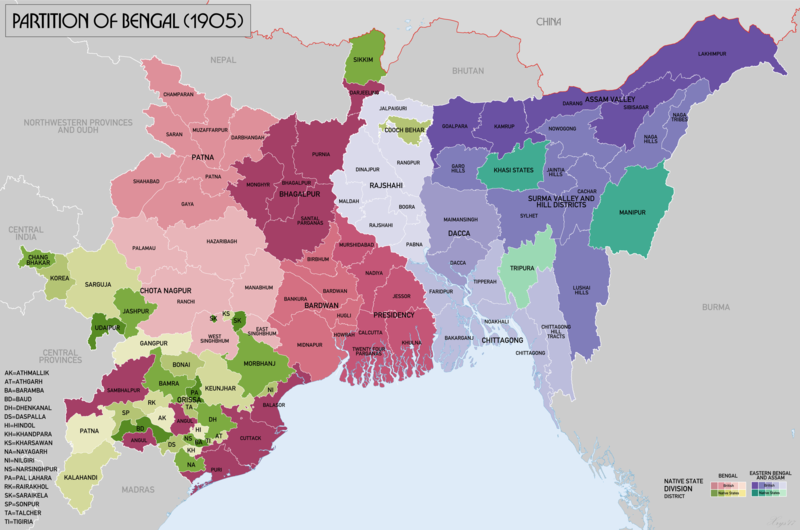

Map showing the partition of Bengal in 1905. Photo Credit

Home, yet, to almost 300 million people of wide ethnic and linguistic diversity, it wasn’t an easy place to manage, with Bengal, the heart of its economic prosperity, proving especially difficult. An intellectual hub of roughly 80 million, the province was an epicenter of political activism, where much of the population, tired of being treated as subservient sources of commodities, advocated for self-rule and greater rights.

Needless to say, the British had no desire for this kind of ethos to spread and take hold throughout the country. To, therefore, curb the rising tide of nationalism, Lord Curzon, the viceroy and governor-general of India, came up with a plan, proposing Bengal be split into two parts, Muslim-majority east and Hindu-majority west.

On the surface, it would be framed as an administrative solution to the problems that come with managing a mammoth province, and indeed that was a motivating factor. Yet the true crux of his purpose was to separate the economically powerful urban areas in the west from the less affluent ones in the east, so the British could maintain a tighter grip on the wealthier and more politically zealous parts of Bengal.

Divide and Conquer

The goal was to divide and conquer—a strategy they had already begun to implement by offering higher education to the descendants of Mughal elites in hopes of cultivating a loyal class who thought they benefited from the empire’s system. A goal, regardless of Muslims’ initial aversion, he managed to initiate, after fanning the small embers of their discontent, reinforcing the idea their interests were distinct and incompatible with that of the dominating threat of Hindu culture.

And, naturally, it worked. In fact, too much.

For when, in 1905, partition officially went into effect, dividing the province — based not on historical ties, relationships, and the needs of the territories involved, but on managerial efficiency — the result was irrevocably tempestuous.

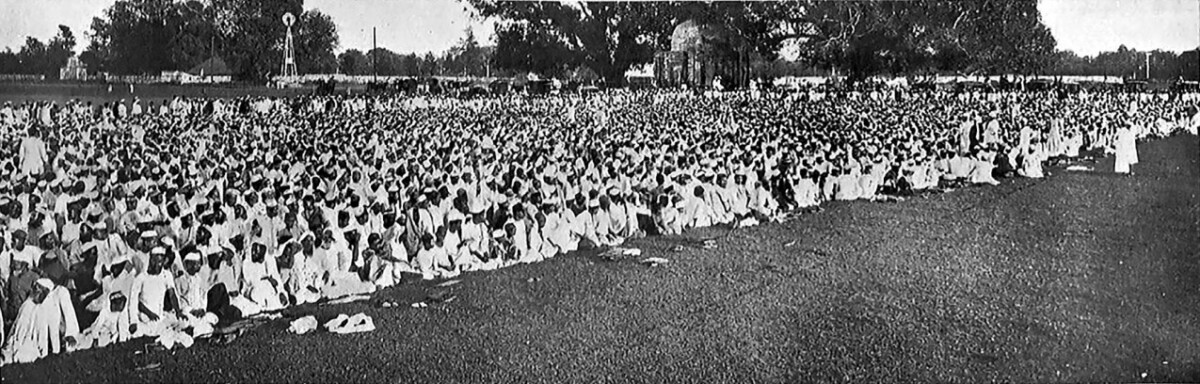

A mass meeting of Muslims gathered in Dhaka in 1906 to show their support for the partition of Bengal.

As expected, Muslims, fueled by an inflated sense of rivalry and mistrust, used the opportunity to develop stronger identity and influence. In essence, this culminated in the founding of the Muslim League, a political party that made clear its interests were different from that of Hindus, exacerbating and institutionalizing cultural fissures through the forging of separate electorates.

Hindus, on the other hand, discerning the oppressive and exploitative nature of the split, didn’t weaken in their nationalistic fervor, like the British intended, but grew only more indignant, calling for a boycott of British goods and institutions, and the promotion of Indian-made products. A movement that spread like wildfire, sparking mass protests and rallies, Muslims responded with counter-rallies and demonstrations of their own, until the British, overwhelmed by the communal and economic disruptions, decided to annul partition in 1911, restoring Bengal to the united province it was prior.

But, of course, it was united in name only, as the damage had already been done.

Muslims, believing they were being relegated to a position of subservience under Hindu subjugation, lost faith in the British administration, thereby increasing their resolve to gain greater sovereignty, and eventually, a separate Islamic state. And Hindus, flushed with the triumph of their efforts, felt profoundly empowered in the dream for independence, stirring a revival of their own religious culture and identity.

As economic, political, and communal tensions thus rose over the next few decades, climaxing with the Partition of 1947 and the redividing of Bengal so its eastern half could join the newly formed Pakistan before ultimately gaining its own independence, things were never the same again.

Once amicable in spirit, the two communities became more polarized than ever, and Bangladesh a tragic arena for their ongoing hostilities.