The status of women across India’s spiritual traditions has been deeply misunderstood over the years, rooted in colonial distortions that cast the country as backward, irrational, and oppressive to justify the subjugation of her land and people.

With the goal of dispelling these misconceptions, we at the Hindu American Foundation launched The Shakti Initiative, an online clearinghouse showcasing Hindu teachings about and by women. Extensive as it is, however, we barely scratch the surface, falling short — perhaps perpetually — of exhibiting the true impact of female saints on our culture.

This, of course, is not for lack of trying. From ancient Vedic texts to modern-day examples, our repository is filled with many such figures, and each year we endeavor to expand it with others equally deserving. So please, join us on this journey of everlasting discovery, for history abounds with countless more awaiting their due honor.

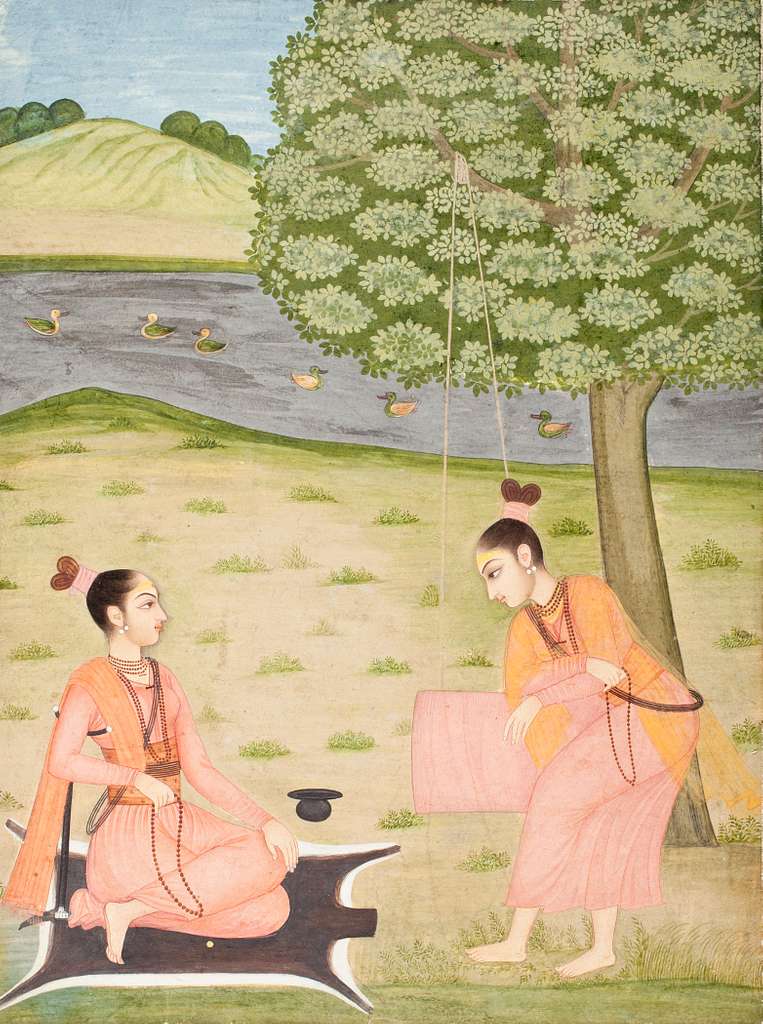

Caption: Two female ascetics share each other’s company by a riverbank beneath a leafy tree in this 18th-century painting. Clad in Saffron robes and adorned with beads, one sits cross-legged on a deerskin while the other appears in motion, possibly approaching or offering service.

Hemalekha

Once, in the ancient kingdom of Dasarna, there lived a prince named Hemachuda, the son of king Muktachuda. One day, while out on a hunting expedition, his party was suddenly struck by a tornado, sending them into a chaotic scramble. As violent winds of rain, dust, and stone shrouded the forest in darkness, he became separated from the others, stumbling upon a nearby ashram for shelter.

There, in the refuge of that place, he met Hemalekha, the foster-daughter of Sage Vyaghrapada. Before long, he was captivated by her beauty and grace, and she too felt drawn to his character, desiring their union. So sensing the mutual attraction, her father gave them his blessings, proposing that they get married, to which they eagerly agreed.

After their wedding, the couple lived cheerfully for some time in the palace, but gradually Hemalekha grew remote and indifferent. Displaying an increasing detachment from earthly affairs, she seemed almost callous in behavior, sparking an anxious Hemachuda to ask about the change of heart. His wife, however, assured him not to worry. Her love for him was still as strong as ever. She simply had turned her focus inward, in search for an everlasting bliss past the transitory fabric of sense gratification. Though, as royalty, they were afforded the greatest of comforts, each pleasure was doomed to fade, leaving in its wake a corresponding distress that leads to the hankering for yet more pleasure. A vicious cycle that fosters dissatisfaction and emptiness, actual happiness, she said, lay beneath life’s volatile waves, amidst the serene depths of one’s eternal essence.

Upon hearing his wife, Hemachuda sank into melancholy. Accustomed as he was to sensory pursuits, he couldn’t denounce them completely. Knowing, still, that her words rang true, he also couldn’t continue the indulgent life he led. Feeling, therefore, aimless and bereft, he begged her for direction.

Needless to say, Hemalekha agreed, prompting him to engage in self-reflection. If, by this process, he could unfasten his ethos of possessiveness, freeing his ego from worldly tethers, then he could understand his true nature, along with the boundless fulfillment that came along with it. Thereby withdrawing to his quarters, Hemachuda began meditating, deconstructing the framework of his identity under his wife’s quiet guidance.

First, he focused on his palace and wealth — the most obvious to discern of his material attachments. From there, he contemplated his position as a prince. Born into royalty, surely his body was an integral aspect of his identity. Yet, made simply of blood, flesh, and bone, its continuous transformation proved its impermanence, while he, as a conscious entity, still felt the same. Perhaps, then, he was the mind? But that too was shaped by his thoughts, which came in unceasing waves, each one different from the last.

Indeed, the more he considered it, the more he realized everything he had identified with wasn’t actually him but a temporary possession connected to his psycho-physical condition. As he thus delved deeper into meditation, cleansing the dust of these misconceptions, his authentic self shimmered clear and true, reflecting his immutable disposition. He was, he discovered, an indelibly spiritual being, tied to a Divine reality that permeated all of existence.

Perceiving its presence, he now felt connected to all things, filling him with a profound sense of harmony that drove him to inherit and look after his father’s kingdom with the utmost care. And as Hemalekha ruled by his side, she too distributed her compassion, teaching Dasarna’s people, just as she had done her husband.

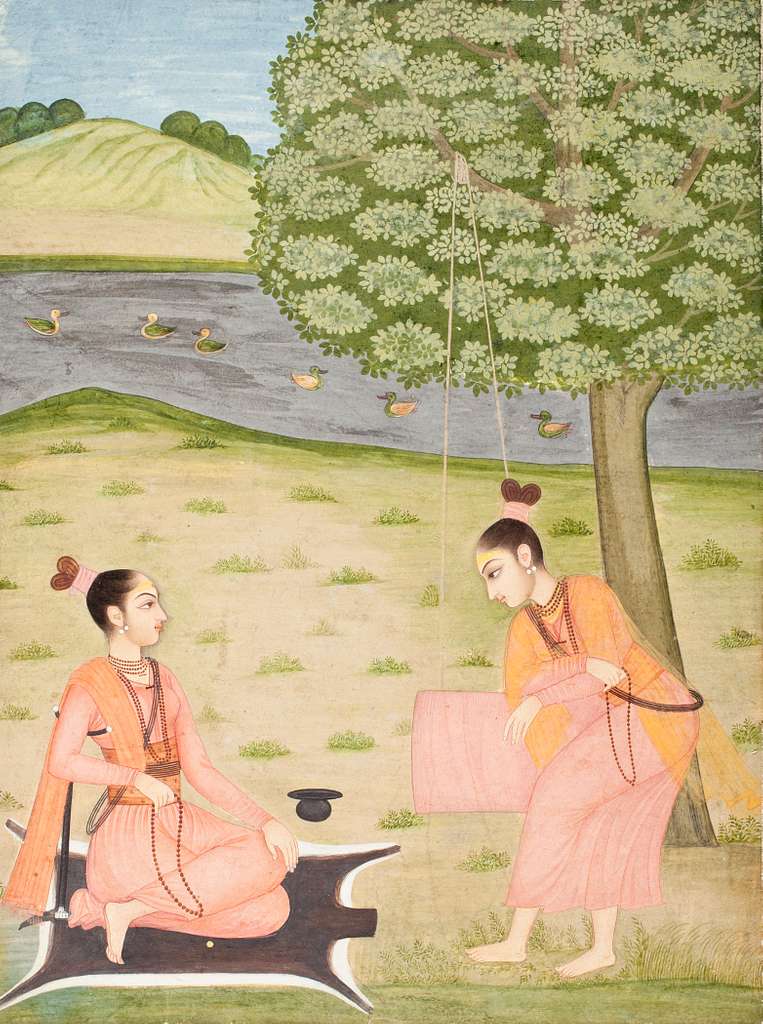

Caption: An 18th-century painting of a female ascetic seated in radiant trance.

Akka Mahadevi

Born around 1130 CE in the Shimoga district of Karnataka, Akka Mahadevi’s spiritual inclinations revealed themselves at an early age, drawn innately toward Shiva, the divine being of transformation. Always immersed in his veneration, her practice was not one of mere custom, nor that of naive sentiment. As she affectionately called him Chenna Mallikarjuna, or “Beautiful Lord, White as Jasmine,” she saw him as more than just the village icon. For her, he was the supreme object of love — to whom she felt eternally bound in the sacred mood of conjugal devotion.

Upon getting older, however, she grew into a beautiful woman, and so there were those who sought to have her for themselves, despite her aversion. One of them, Kaushika, was a powerful Jain ruler who wouldn’t take no for an answer. Persistent in his advances, Mahadevi was eventually forced to relent, but not without setting certain conditions. If he was to be with her, she said, he must grant her the freedom to continue in her devotion, allowing her to associate with scholars and saints, regardless of their gender. Eager as he was for their union, he swiftly agreed, thereby making arrangements for them to be wedded.

It wasn’t long, naturally, before Kaushika realized their marriage wouldn’t yield the results he was hoping for. While he was a superficial man engrossed in sensory pursuits, Mahadevi operated on the plane of transcendence, wholly uninterested in the fruits of materialistic pleasure. Spurned, ergo, in one attempt after the next to control her, he soon reached a breaking point, demanding she give up her spiritual path altogether. Unwilling, of course, to do such a thing, she instead did the opposite, abandoning her post as queen and all of the luxuries that came with it. The mundane tethers of money, power, and comfort, would hold her back no more. From that moment henceforth she would walk the earth naked, living a life of total surrender to Shiva — body, mind, and spirit.

In search of fellow devotees, her wanderings brought her to the town of Kalyana, where she met Basavanna and Allama Prabhu, two sages of towering spiritual acumen. Though, at first, they received her with skepticism, the latter ultimately accepted her as a disciple, providing the guidance she craved to further her practice and dedication. Deepening the profound depth of her devotion under his tutelage, she earned the respect of all the town’s seekers, some of whom came to revere her as “elder sister,” regardless if she was younger than them. And while she relished their association, giving the gift of her presence for a while, the time soon came for the next phase of her journey.

Thus departing their company, she traveled to the hills of Srisailam, where she entered the forest of Kadali. There, amidst nature’s elements, she lived out the rest of her life in complete dependence on Shiva, begging for food, drinking from streams, and sleeping in the ruins of ancient temples. Absorbed without hindrance in meditation of her beloved, she composed hundreds of poems in his honor, which flowed effortlessly from her lips in rapturous trance. Replete with intimate details of sacred longing and union, they are a window into her unique devotion. They are her offerings, her heart — and they’re enduring proof that Divinity’s love transcends all boundaries of societal convention.

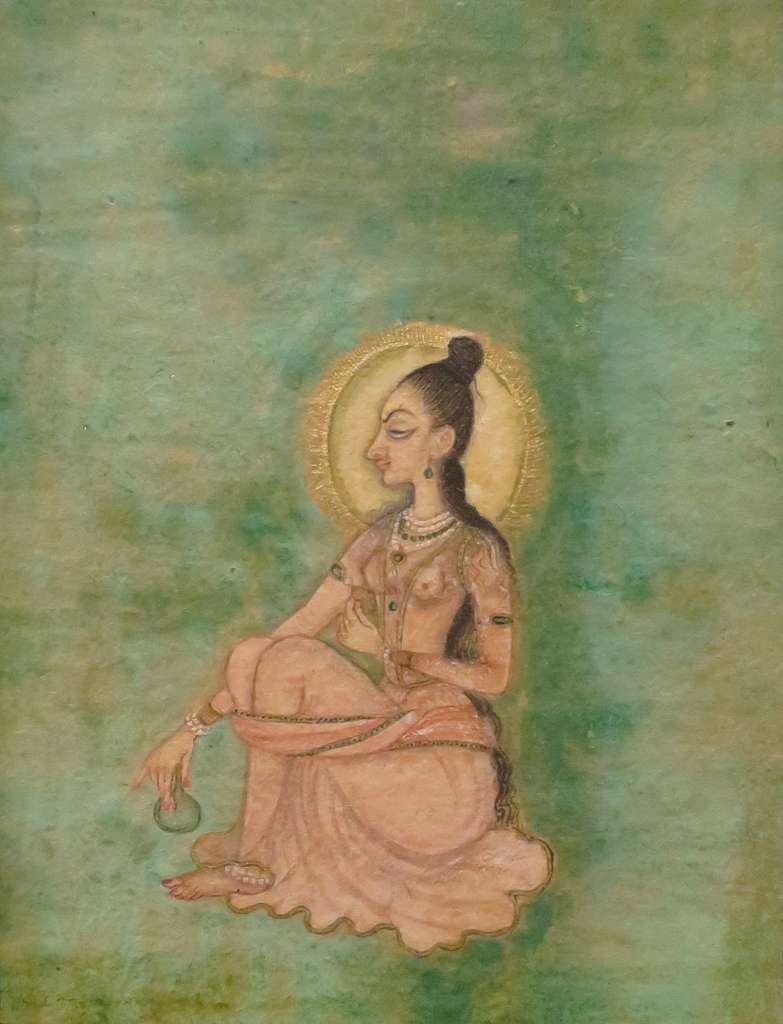

Caption: An 18th-century painting of a woman venerating a Shiva linga, while another plays the mridanga, a drum traditionally used in Hindu devotional music.

Anandamayi Ma

She came into the world in 1896, to impoverished parents of Kheora, a small village in present-day Bangladesh. Given the name Nirmala, meaning “spotless” or “pure,” her nature exuded a quiet radiance, unfazed by life’s volatile flurries, including the tragic deaths of her siblings. And while this led some to think she might be mentally underdeveloped, especially considering her lack of education, her indifference was unequivocally a product of her sacred disposition, as revealed in the progression of her luminous life.

Per the custom of the time and region, she was wedded at 13, but didn’t live with her husband until 18, when she joined him in Ashtagram, where he had procured stable work and established a home for them. During this period he attempted to consummate the marriage, but she made it clear she had no interest in conjugal affairs, transforming into a corpse-like state in response to his advances. Though, at first, he was disturbed by her reactions, he soon came to respect her spiritual calling, submitting to a union of celibacy. Thereby free to be herself uninhibited, Nirmala leaned more and more into her practice, exhibiting rapturous episodes while in the depths of her devotion.

At first, such ecstasies occurred in private, but eventually spilled out to the public when witnesses saw her fall into a spiritual trance of supernatural effects. As these displays grew progressively common, particularly while she was participating in kirtan, or devotional singing, word spread far and wide, drawing curious seekers to her company. Before long she had developed a following, many of whom believed she was an embodiment of the Divine, calling her Anandamayi Ma, or “The Joy-Permeated Mother.” Indeed radiating a palpable bliss, even eminent scholars became her disciples, including Varanasi’s Sanskrit College principal, Gopinatha Kaviraja, and Jadavpur University’s vice chancellor, Triguna Sen.

Stamped, therefore, with a veritable air of legitimacy, many more flocked to her presence over the years as she traveled throughout India, establishing ashrams, shrines, and a variety of spiritual communities. Teaching with luminous clarity, charm, stillness, and humor, she met people where they stood, guiding those of all backgrounds and philosophical leanings — be they Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, Christians, or Jews.

It didn’t matter that she was illiterate. And it definitely didn’t matter that she was a woman. By the time she passed away in 1982, she had amassed thousands of disciples, all united by her light and spirit. Today, they carry her legacy forward, inviting all to bask in her presence. For though she’s gone, she lives through her compassion, felt by those in service to her devotional will.